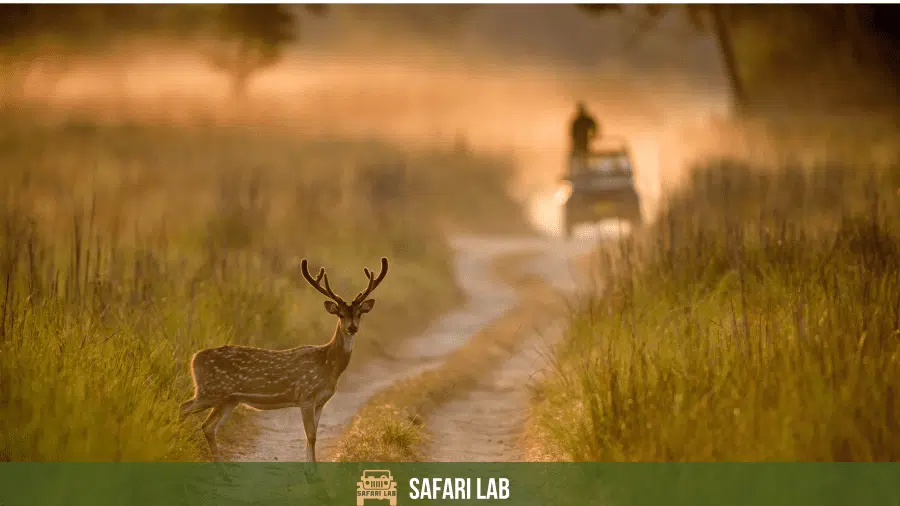

Thattekad—an unassuming name, tucked quietly in the western foothills of Kerala’s Anamalai range—rises in significance the moment one hears a bird call echo through its canopy. This is Thattekad Kerala, home to the famed Thattekad Bird Sanctuary, a place where stillness is alive, where every rustle speaks, and the trees wear birds like blossoms.

Known formally as the Dr. Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary, this mosaic of tropical forest, marshland, and riverine habitat was first identified by India’s most beloved ornithologist in the 1930s. Salim Ali called it the “richest bird habitat in peninsular India”—a title it still wears with quiet pride. Here, nature hasn’t raised its voice in alarm; it sings, softly and constantly, a lullaby of continuity.

Bordered by the Periyar River on either side, Thattekad isn’t vast by Indian standards. It spans just over 25 square kilometers. But within this living emerald, over 300 species of birds have taken residence—some elusive, others unabashed, and all woven into the rhythm of the forest. You don’t just come here to see birds. You come to feel time slow down to the beat of a drongo’s wings or the low hum of a frogmouth’s breath.

Thattekad is not a place you pass through on the way to Munnar or Thekkady. It is the destination itself—for those who listen, for those who linger, for those who want to remember what the world sounded like before it got too loud.

What is Thattekad Bird Sanctuary?

Spread across 25 square kilometers, Thattekad bird sanctuary is among Kerala’s first and most biologically diverse protected areas. It was declared a bird sanctuary in 1983, four decades after Dr. Salim Ali’s pioneering survey that revealed its exceptional avifaunal richness. His astonishment then still resonates today, as modern birders and ecologists continue to discover species both known and rare, often within hours of entering the forest.

It is not grand in size—but like a well-composed poem, it carries depth that belies its scale. Cradled between two arms of the Periyar River, its terrain forms a natural sanctuary, a layered habitat of lowland evergreen forest, bamboo thickets, and gently flowing streams. At dawn, mist curls through the undergrowth like breath from the forest itself.

Unlike the open grasslands of the north or the dry deciduous forests of central India, Thattekad’s ecosystem is dense, moist, and resonant. The forest here isn’t passive—it teems. Within a single hectare, a visitor might pass a Malabar giant squirrel, a flame-throated bulbul, and a silent owl perched in a sunbeam. In the wetter patches, one may spot amphibians still unnamed by science. The sanctuary has even recorded seasonal visits from the elusive Indian elephant and leopards moving through the buffer zones at dusk.

The biodiversity here is intricately layered: tall emergent trees give shelter to canopy dwellers, while the understorey thickets host insectivorous birds and ground-foraging species. Epiphytes and lichens lace the trunks, drawing moths, which in turn invite nightjars and owls. Everything here exists in relation—intimate, complex, and finely tuned.

The Birds of Thattekad

Step softly, and you may hear it before you see it—the rustle of feathers, the chime of unseen wings. In Thattekad, the birds do not merely inhabit the forest. They compose it. Each species, a note in an ancient score. Each call, a message shaped by millennia of rain and leaf and sun.

Elusive and Rare Sightings – Is this your lifer?

Tucked in the dimmest pockets of the forest, the Sri Lanka Frogmouth rests motionless on a low branch, its bark-patterned plumage making it almost indistinguishable from the tree. A shy, nocturnal relic of Gondwanaland, it is not uncommon here—but never easily seen. Nearby, if one is both patient and extraordinarily fortunate, the eerie call of the Sri Lanka Bay Owl may rise from the shadows—its rounded, heart-shaped face emerging like a mask in the torchlight of early dawn.

The Malabar Trogon, with its crimson belly and emerald-green back, flits through the mid-canopy in swift, deliberate motion. Once you’ve seen one, you understand why birders travel continents for a glimpse. No less evocative is the White-bellied Treepie, restricted to the Western Ghats. Its restless calls break the hush of the upper branches like laughter in a cathedral.

The Nilgiri Wood Pigeon, Wynaad Laughingthrush, and the often-overlooked Crimson-backed Sunbird also belong to this southern fold of the subcontinent—endemic, resilient, and increasingly rare. Each sighting feels like a secret shared only with those who linger long enough to learn the forest’s rhythms.

The More Common, Yet Brilliant Bird Sightings

Yet Thattekad is not only a refuge for the rare. It is alive with birds that fill the forest with movement and song. The Indian Pitta, bold and impossibly colourful, arrives with the pre-monsoon breeze, its “Wheee-chooo” whistle bouncing through the bamboo groves. It hops like a jewel fallen into leaf litter, turning over the earth for worms.

You’ll see the Greater Racket-tailed Drongo, its long, curling tail-streamers trailing behind like a dancer’s ribbons. It mimics the calls of other birds and even squirrels, creating a polyphony that seems more mischief than mimicry. The Malabar Grey Hornbill, social and conspicuous, haunts fruiting fig trees, its bark-like call echoing through the valleys.

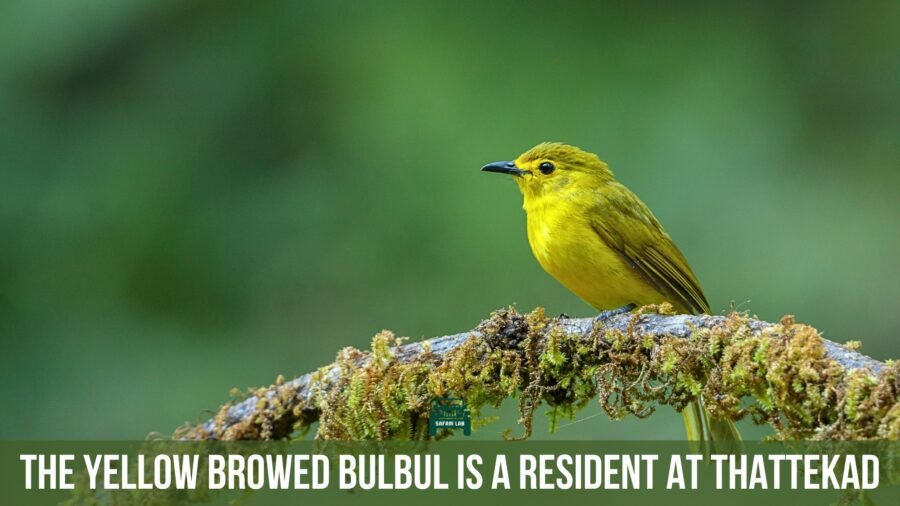

The forest paths often bring sightings of the Heart-spotted Woodpecker, scaling rough bark with its stiff tail braced against the trunk, and the chattering parties of Yellow-browed Bulbuls, bright-eyed and ever-alert. Along the water’s edge, Common Kingfishers, Little Cormorants, and Indian Pond Herons wait in practiced stillness.

These birds are not merely common; they are foundational. Without them, the forest would lose its music. With them, Thattekad becomes what it is—not a wilderness untouched, but a wildness still intact.

In Thattekad, birdwatching becomes more than a checklist activity. It becomes an act of reverence—an understanding that the forest is not just scenery but living history, unfolding moment by moment in the flight paths above and the rustles below.

Planning Your Visit – A Birder’s Guide to Thattekad

To visit Thattekad is not merely to arrive at a forest, but to step into a world of patient time—one that rewards the observer who is willing to rise with the sun, to walk without speaking, and to listen. Truly listen.

When to Go: Timing the Song of the Forest

The best time to visit Thattekad is during the dry months between November and early March. In this window, the sanctuary is at its most generous. Migratory birds, having crossed continents, arrive to rest and feed. The undergrowth dries just enough to make walking easier, but the air still carries the weight of recent monsoons—rich, green, alive.

By April, the heat begins to settle in. Bird activity slows through the middle of the day, but even then, in the hush of early morning and the golden light of evening, sightings continue—more quiet, more patient. The monsoon, from June to September, brings a different mood. Heavy rains swell the Periyar, and many trails vanish beneath the water. But the forest sings differently then, in frog calls and dripping leaves. Not ideal for birders perhaps, but still deeply alive.

How to Reach Thattekad: A Journey Inward

Thattekad sits quietly, away from Kerala’s louder tourist circuits, in the Ernakulam district. It is closest to the town of Kothamangalam, about 13 kilometres away.

Those arriving by air will land at Cochin International Airport, just under 40 kilometres distant. From there, the road climbs gently toward the forest, following the contours of the Periyar River, through rubber plantations and small homesteads. A hired car or pre-arranged taxi is the most seamless option. Buses do ply from Kochi and Aluva, though their timings are best suited to the unhurried.

The nearest railway station lies in Aluva, from where a road journey of about 90 minutes will bring you to the sanctuary gate.

How Long to Stay: Time Measured in Wings

To truly begin to know Thattekad, allow for two to three full days. The forest does not give up its secrets to the hurried. Some birds, like the Indian Pitta or the Bay Owl, might only appear once in that time. Others, such as the racket-tailed drongo or the flameback woodpecker, reveal themselves daily, but never in the same place twice.

Multiple trails criss-cross the sanctuary—some well-trodden and official, others known only to the local guides who’ve grown up under these trees. Morning walks are essential. Afternoons can be used to rest, review field notes, or explore quieter parts of the buffer zone.

Hiring a birding Guide: The Eyes of the Forest

Thattekad is not an easy forest for the untrained eye. Many of its birds are masters of camouflage or habitually silent. Local guides, many of whom have learned their craft over decades, are invaluable companions here.

Walks typically begin at first light. The forest changes every hour: owls returning to roost, babblers waking the canopy, drongos darting in pursuit of invisible insects. Most guides offer both morning and afternoon sessions, each lasting about three hours, with routes tailored based on recent sightings and seasonal changes.

If you’re seeking something specific—a nightjar, perhaps, or a trogon—mention it. The guides will know where they were last heard, last seen, last suspected.

What to Carry: Tools for Stillness

The most important thing to bring is silence.

But practically, binoculars (8×42 or 10×42) are essential. A field notebook, a local bird guide (digital or print), and a water bottle should always be with you. Dress in earth tones—greens, browns, greys—anything that allows you to fade gently into the forest’s palette.

Footwear should be sturdy but quiet. Mornings are cool, so a light layer helps. Insect repellent is recommended, especially near the water. Camera users will want a telephoto lens; but the best sightings often happen close, in the kind of light that doesn’t require anything more than an open eye.

Pacing Your Visit: The Rhythm of the Day

Early mornings begin around 6:30 AM, just as the mist begins to lift. This is when the forest stirs, when movement in the canopy is matched by sound—a crescendo of calls: hornbills, mynas, bulbuls. A mid-morning break allows time to rest and record.

Evening walks begin around 4:00 PM. Light softens, and the shadows stretch. This is when you might glimpse an owl in flight or watch a kingfisher return to its roost.

Evenings are quiet at Thattekad. There are no loud resorts, no nightlife. This is a place where the day ends with frogcalls and the rustle of fruit falling into leaf litter.

Where to Stay – Thattekad Resorts and Homestays

To spend a night in Thattekad is not merely to find shelter—it is to sleep beneath a canopy woven with stars and sound. It is to lie still as the forest continues around you, soft-footed and unhurried. Accommodations here are not separate from the sanctuary; they are part of its extended rhythm. Whether you stay in a river-facing tent, a modest family homestay, or a lodge set into the forest fringe, the pulse of the wild remains close.

Where the River Runs Quiet – Thattekad Resorts

Just beyond the forest’s edge, overlooking the slow, meandering Periyar, lies Soma Birds Lagoon—a property as much a birding basecamp as a retreat. Here, mornings begin with the piping notes of a White-cheeked Barbet and the flash of a Malabar Parakeet just outside your window. The rooms are spaced out across old plantations, each one named after a local bird, a quiet tribute to the land it rests on.

Not far from there, Hornbill Camp sits low and discreet, a cluster of luxury tents on wooden platforms. Guests are close enough to the river to hear the splash of otters and the slap of wings as egrets rise. The camp is entirely solar-powered, and its naturalists are some of the most experienced in the region—guides who can identify a trogon’s call from fifty metres away without turning their head.

Further upstream, Periyar River Lodge offers a more secluded, cottage-style experience. With only a handful of rooms and an emphasis on slow travel, it is the kind of place where breakfast is delayed because a Malabar Grey Hornbill has landed on the jackfruit tree by the porch.

Among Locals, Beneath the Canopy – Thattekad Homestays

To understand Thattekad, one must also listen to its people. And for that, a homestay is ideal. Jungle Bird Homestay, operated by a family of naturalists just minutes from the sanctuary gate, is more than a place to sleep. It is a place where stories gather. Guests sit with binoculars over breakfast, reviewing their morning sightings with the hosts, who’ve been watching these birds since childhood.

Then there is Bird Song Homestay, modest and warm, tucked into a quiet road where the loudest interruption is likely to be a racket-tailed drongo making a mockery of nearby squirrels. Here, birders often return year after year, not only for the species list, but for the kindness of the hosts and the comfort of familiar tea shared under the shade of an areca palm.

For those seeking a more independent setup, Fish Valley Homestay offers a fully equipped two-bedroom cottage beside a small lagoon. The mornings here unfold slowly, with Purple Herons stalking the water’s edge and kingfishers flashing like jewels across the surface. At night, the forest draws close—first in frog calls, then the distant boom of an owl.

Where the Forest Breathes – Thattekad Camps

Closer to the sanctuary’s periphery, and sometimes nestled within its buffer zone, are smaller eco-camps that offer a more immersive stay. Birds Murmur Camp near Njayappilli, with its elevated canvas tents and outdoor showers, is a favorite among photographers and researchers. It offers no distractions—just the whisper of bamboo leaves and the steady rhythm of cicadas in the afternoon heat.

Here, the power may flicker, but the birds never miss a beat. In one recorded visit this past February, a guest at the camp logged over 95 species in three days—among them, the Malabar Whistling Thrush, the Indian Paradise Flycatcher, and a surprise sighting of the Black Baza circling above the tree line.

Thattekad does not boast five-star hotels or crowded tourist enclaves. What it offers instead is presence—accommodation that complements the forest, rather than competes with it. To stay here is to live, however briefly, in the tempo of wingbeats and rustling leaves. It is not where you come to escape the world, but where you remember it.

Local Insights and Natural Encounters – What the Guidebooks Won’t Tell You

Spend more than a few hours in Thattekad and the forest begins to open up—but only if you’re paying attention. Not just to the trees and the birds, but to the people who move among them every day. The guides here are not just trained—they’re embedded. Many of them were raised in homes where the morning alarm was the call of a Malabar Grey Hornbill, and family stories begin with “the day we saw the Bay Owl”.

Take, for instance, Jijo, one of the most respected local birding guides, often recommended on TripAdvisor and featured in YouTube vlogs by visiting birders from Europe and the US. In February 2025, a group guided by Jijo spotted over 87 species in a single morning session—including the Indian Pitta, White-bellied Treepie, Malabar Trogon, Heart-spotted Woodpecker, Grey Junglefowl, Rufous Babbler, Yellow-browed Bulbul, and the Black Baza circling high above the canopy.

The Kind of Sightings That Aren’t in the Checklist

One YouTuber from the UK, who spent five days in Thattekad in March 2025, described it as “the most thrilling birding experience I’ve had in South India.” They logged 140+ species, but more memorable than the count was the setting: a pair of Sri Lanka Frogmouths nesting just metres from the Hornbill Camp kitchen, unbothered by human movement, their beaks barely visible through the veil of low foliage.

Another birder, staying at Jungle Bird Homestay, was led at dusk by his host to a known Bay Owl roost—no formal trail, no signage, just local knowledge. After a 40-minute wait in near-darkness, the owl appeared—silent, haunting, unmistakable.

Then there are the unexpected encounters. A flock of Ashy Minivets, far from their usual route, passing through Thattekad in January—a possible spillover from nearby Thattekkadu Reserve. A pair of Velvet-fronted Nuthatches, calling loudly while descending the trunk of a rain-drenched gulmohar. These are the moments Thattekad offers—not packaged, not predicted.

Tips from the Field: What Birders Know That Others Miss

- Don’t stick to the official trails. While the Salim Ali and Baza trails are excellent, the real action often lies in buffer zones and village paths. Local guides will take you there—but only if you ask.

- Evenings are underrated. While most birders focus on early mornings, post-4 PM walks often yield raptors returning to roost, and treepies moving in noisy flocks through the upper canopy.

- Stay longer if you want the elusive ones. The Ceylon Bay Owl, Mottled Wood Owl, and Malayan Night Heron have all been sighted here in 2024–25, but rarely on day trips. One guest in April 2025 spent four nights and saw all three.

- Some of the best sightings happen near the homestays. Don’t ignore the trees right outside your cottage. Indian Paradise Flycatchers, Chestnut-headed Bee-eaters, and even the occasional Brown Wood Owl have been sighted within homestay compounds.

- Rain is not your enemy. Light rain in the early hours stirs the understorey birds—like the Indian Blue Robin and White-rumped Shama—into brief but spectacular visibility.

Thattekad Bird Sanctuary, When You Let It Speak to You

Thattekad doesn’t give up its secrets to the rushed traveller. But to those who sit still long enough, who follow the guide who knows where the old nest is, who walk slowly under the same trees each day—it reveals more than you expect.

Not just species names. But behaviours. Patterns. Life.

Conclusion – The Quiet Majesty of Thattekad bird sanctuary

There are forests that dazzle and forests that roar. And then there is Thattekad—a place that does neither. Instead, it listens.

It listens to its birds, hundreds of them, each with a call shaped not for us but for the forest itself. It listens to its river, flowing softly between the Periyar’s arms. And it listens to the few travellers who come here not to conquer nature with cameras or checklists, but to understand something older, quieter, and far more intricate.

You don’t come to Thattekad for spectacle. You come to see a Sri Lanka Frogmouth blink slowly in the dark. To hear a drongo imitate three birds in a row just to show it can. You come because someone told you about a Bay Owl that hasn’t moved from the same roosting branch for days—and because you believe in the kind of waiting that feels like reverence.

There are places in India where wildlife shouts for attention. This isn’t one of them. Thattekad is for the watcher, the listener, the patient. It’s for those who walk the same trail twice because they know the second time might show them what they missed the first.

And when you leave, you do so not with the sense of having ‘done’ a sanctuary, but of having passed through something still unfolding—something wild and alive that allowed you, briefly, to be part of its rhythm.

That, in the end, is the gift of Thattekad bird sanctuary.