Across the rolling savannahs of East Africa, beneath skies vast and unchanging, a drama unfolds — ancient, immense, and eternal. This is the Great Migration, one of the last and greatest wildlife spectacles on Earth.

Each year, more than 1.5 million wildebeest, joined by hundreds of thousands of zebras and gazelles, embark on an epic journey — not in a straight line, but in a ceaseless, circular pilgrimage dictated by the rains. From the short grass plains of the southern Serengeti to the treacherous waters of the Mara River, these animals follow the ancient rhythm of life written not in calendars, but in the land itself.

In this article, we’re diving deep into this natural phenomenon: how it works, when and where to see it, and how not to miss the good stuff (like crocodiles in ambush mode or 500,000 baby wildebeest dropping in just a few weeks).

What Is the Great Migration?

The Great Migration — also known as the wildebeest migration — is one of the most astonishing natural events on our planet.

Stretching across the endless plains of Tanzania’s Serengeti and Kenya’s Masai Mara, this epic journey is not a once-a-year event, but a ceaseless cycle — a vast, living loop in which more than two million animals march onward, driven by hunger, rain, and instinct as old as the Earth itself.

At the heart of this movement are the wildebeest — shaggy, horned, and often underestimated — joined by zebras, gazelles, and eland, all moving in concert across nearly 1,800 miles of grassland, woodland, and treacherous river crossings.

There is no start and no end. Instead, the Great Migration follows the rhythm of seasonal rains. When the rains come, the grasses grow, and the herds gather. When the land dries, they move. Each step is a response to the land — to the whisper of new shoots, to the cooling wind before a storm, to the ancient call of survival.

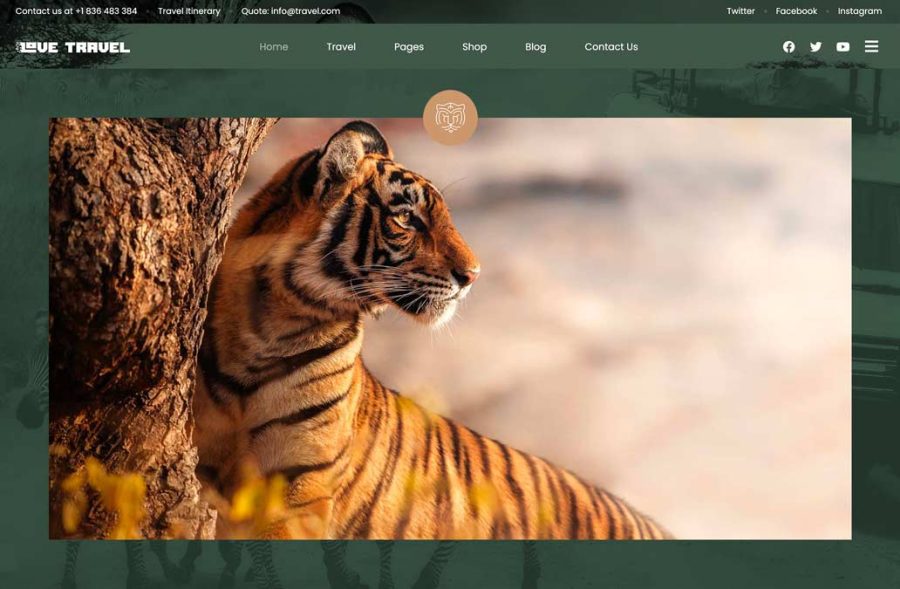

And with them follow the predators: lions, hyenas, cheetahs, and crocodiles, each playing their part in the delicate balance of life. For the Great Migration is not merely a spectacle of movement — it is the beating heart of East Africa’s ecosystem, sustaining life at every level of the food chain.

Why Is the Great Migration So Important?

To understand the importance of the Great Migration, one must look beyond the sheer numbers — beyond the rivers crossed, the predators evaded, the grasslands trampled by countless hooves. The true significance lies in what it represents: an ecosystem still intact, functioning almost exactly as it did thousands of years ago.

The migration breathes life into the land. As the herds move, they graze, fertilise, and reshape the very fabric of the savannah. Their movement ensures that grasslands regenerate, that soils remain rich, and that predators — from lions and leopards to vultures and beetles — have food to sustain them. It is, quite literally, the engine of the ecosystem.

But this is more than a biological chain reaction. It is a testament to what the natural world once was, before fences, highways, and expanding human settlements hemmed in the great migrations that once spanned continents. From the North American bison to the Mongolian gazelle, most large-scale animal migrations have disappeared.

This one remains.

Where and When Can You See the Great Migration

As we mentioned earlier, the Great Migration has no start or stop point. Its an endless cycle constantly in motion. The herds are moving somewhere as you read this.

But with some planning and know how, you can maximize your chances of spotting this amazing phenomenon in action.

January to March — Calving Season in the Southern Serengeti

As the year begins, the great herds are drawn southward, deep into the Ndutu region of the southern Serengeti and the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. Here, the short rains have transformed the plains into a lush expanse — green, tender, and bursting with promise.

It is here that the wildebeest give birth.

Within the space of just a few short weeks, an estimated half a million calves enter the world. Day by day, they emerge — fragile, trembling, yet astonishingly quick to their feet. Within minutes of birth, a newborn wildebeest is walking. Within hours, it is running — for it must.

This is not merely a time of renewal. It is a time of danger.

Predators, too, know this rhythm. Lions, hyenas, cheetahs, and jackals are drawn to the abundance, and they wait patiently in the tall grasses. But here, sheer numbers offer protection. With so many young born in such a brief span, the odds shift — a strategy known in nature as predator swamping. While some calves will fall, many more will survive.

The plains during this time are alive with sound — the bleating of calves, the low grunts of protective mothers, and the distant roars of opportunistic predators. It is a place of tenderness and of tension. Of beginnings… and of the balance of life.

- Best region to witness this: Ndutu and Lake Masek area

- Wildlife highlights: Calving herds, predator action, thousands of newborns

- Seasonal notes: Short rains have ended, leaving behind lush grass and dramatic skies

April to May — The Long March to the Western Corridor

With the arrival of April, the southern plains of the Serengeti begin to dry. The verdant flush that welcomed new life begins to fade, and with it, the herds — now swollen in number with countless calves — turn northwest, drawn toward distant storms and the promise of renewal.

This is a time of movement, not spectacle. A quiet phase, yet no less vital. The great herds begin their long migration through the central Serengeti, stretching in ragged, restless columns that seem to flow endlessly across the horizon. Dust rises beneath their hooves, as wildebeest, zebra, and gazelle march side by side in one of the Earth’s most synchronized exoduses.

They move steadily toward the Grumeti River, a waterway that will soon challenge them with its own hazards. But for now, their journey is not yet defined by predators or perilous crossings — it is marked by endurance, by the rhythm of hooves, and by the pull of instinct.

Overhead, the skies shift. The long rains begin, nourishing the Western Corridor and inviting new grass to spring forth. And once again, the herds will follow.

Though this phase is often overlooked by those who chase drama, it is in many ways the most pure expression of the migration’s purpose — a steady, ancient movement governed by the subtle dance between rain and grass, need and response.

- Best region to witness this: Seronera (Central Serengeti), heading into Grumeti

- Wildlife highlights: Large herds on the move, frequent sightings of elephants, leopards, and hyenas along the way

- Seasonal notes: The long rains begin — landscapes are lush, and camps may be fewer as some close temporarily

June to July — The Northern Push and the Mara River Crossings Begin

As the rains sweep across the western Serengeti, the herds continue their advance — not merely grazing, but surging forward, compelled by an ancient urgency. The land begins to dry once again, and the herds, numbering in the millions, begin to converge upon the north.

By late June, the front runners have reached Kogatende and Lamai, in the northern Serengeti. The terrain here is more rugged, the grass shorter, and the predators bolder. The Mara River lies ahead — wide, brown, and treacherous — and it is here that the most dramatic scenes of the migration will soon unfold.

It begins subtly. A pause at the riverbank. Hooves churning dust. The herd gathers in growing numbers. Tension builds. And then, without warning — a single wildebeest leaps.

What follows is chaos.

Thousands of animals plunge into the river, churning the water with frantic limbs. The current is swift, the banks steep, and the crocodiles, massive and ancient, lie in wait. Not all will make it to the far side.

These Mara River crossings, which begin in earnest from mid-July, are among the most iconic wildlife spectacles on Earth. They are not scheduled events, but spontaneous, primal bursts — dictated by the instincts of the herd and the perils of hesitation.

And yet, for every life lost, thousands survive — driven onward by hunger and a force that no map or compass can explain. This is survival through motion, a truth played out in the most vivid theatre imaginable.

- Best region to witness this: Northern Serengeti (Kogatende, Lamai)

- Wildlife highlights: Mara River crossings, crocodile ambushes, lion pride territories

- Seasonal notes: Clear skies, excellent visibility, and the beginning of peak safari season

August to October — The Masai Mara Takeover

By August, the wildebeest have crossed into the Masai Mara, a landscape rich with life and shadowed by danger. The grass here is shorter, the vegetation more open, and the concentration of predators unparalleled. For the migrants, it is both a sanctuary and a hunting ground.

This is the most celebrated phase of the Great Migration — where Africa’s vast herds meet one of its most iconic wildernesses. The plains ripple with movement as wildebeest graze, restless and alert, watched always by the golden eyes of lionesses hidden in the grasses, and leopards perched silently in the branches above.

The Mara River, winding through the reserve, still holds the threat of late-season crossings. Herds hesitate, reverse, and return — the decision to cross never made lightly, for every plunge into the water may be their last.

And yet, there is a surprising serenity here too. The land is generous. Calves born months ago now run with strength. Zebra stallions keep vigilant watch over their harems. Topi and eland stand in stoic stillness. And through it all, the wildebeest continue to move, never staying long, always listening — for rain, for danger, for the call to return.

This period, from August through October, is the most accessible for visitors. The wildlife is concentrated, the skies are clear, and the predators are active — making it one of the finest times to witness the interplay between life and death on the African plains.

- Best region to witness this: Masai Mara National Reserve and the Mara Triangle (Kenya)

- Wildlife highlights: Big cats in action, river crossings, herds spread across the plains

- Seasonal notes: Peak tourism season — advanced bookings are essential

November to December — The Return to the Serengeti

As the short rains return to the southern Serengeti, the air changes. The scent of damp earth rises. Shoots of new grass begin to pierce the soil. And far to the north, the herds — sensing the shift as they always have — begin their journey home.

This is the quiet phase of the Great Migration, one often overlooked by those who seek only spectacle. But here, in this movement southward, lies the essence of the migration’s enduring mystery. There are no fences, no guides to show the way. And yet, they return — precisely, as they have for centuries.

From the northern reaches of the Masai Mara, the wildebeest move swiftly through the eastern corridor of the Serengeti, passing through Namiri Plains, Seronera, and eventually arriving in the Ndutu region once more. The grass here, nourished by the rains, is fresh and rich — a reward for the journey, and a promise of what is to come.

By December, the herds have begun to settle once more. The circle nears completion. In a matter of weeks, the females will begin to give birth, and the plains will once again echo with the bleats of newborn calves.

The migration never ends. It does not pause. It simply flows — ever forward, ever returning — in a dance as old as the land itself.

- Best region to witness this: Eastern and southern Serengeti, including Ndutu

- Wildlife highlights: Herds in motion, early predator activity, shifting weather patterns

- Seasonal notes: Fewer tourists, green landscapes, ideal for peaceful sightings

The Great Migration FAQ

Q. When is the best time to see the Great Migration?

A. The Great Migration is not confined to a single moment in time. It is a continuous, circular movement, unfolding across the Serengeti and Masai Mara throughout the year — each phase revealing a different facet of this extraordinary journey.

January to March brings the herds to the southern Serengeti. Here, the rains have fallen, and the plains are rich. It is calving season — a time of birth, abundance, and intense predator activity.

April to May marks the beginning of movement. The herds set off towards the Western Corridor, drawn by distant storms and fresh pasture. Though less dramatic, this is the migration in its purest form — quiet, nomadic, and deeply ancient. The land, nourished by the long rains, is at its most verdant.

By June and July, the herds reach the Grumeti and Mara Rivers, and with them, the first river crossings. Tension builds, and predators lie in wait.

In August and September, the migration spills into Kenya’s Masai Mara, where it reaches a dramatic crescendo. Lions hunt, crocodiles lurk, and the plains teem with life.

October brings the beginning of the return. The herds grow restless. The rains to the south begin once more.

And in November to December, the circle closes. The herds move back into the Serengeti, following the rhythm that has guided them for generations.

There is no single “best” time — only the right moment for the story you wish to witness.

Q. Where is the best place to witness the wildebeest migration?

The Great Migration moves in a vast, looping circuit between Tanzania’s Serengeti and Kenya’s Masai Mara. To witness it is not merely a matter of being present, but of being in the right place at the right time.

In the early part of the year — January to March — the southern Serengeti and Ndutu region offer a front-row seat to the calving season. Here, the grass is green and rich, and predators gather for the feast.

During April to May, the herds pass through the central and western Serengeti, making their way toward the Grumeti River. This is a time of long-distance movement and a quieter, more meditative experience of the migration.

From June to July, the migration reaches the northern Serengeti — the stage for the famed Mara River crossings, where drama unfolds in every plunge and predator watches from the riverbank.

In August to October, the herds occupy Kenya’s Masai Mara, a smaller, denser ecosystem teeming with big cats and scavengers. The Mara Triangle offers particularly vivid viewing, with fewer crowds and abundant wildlife.

And from November onward, the herds move back south through the eastern Serengeti, preparing to complete the cycle once more.

Each region offers a different vantage point — one may offer spectacle, another serenity. But all are threads in the same magnificent tapestry. The “best” place is the one that aligns with the moment you wish to witness in this ancient journey.

Q. Are Mara River crossings guaranteed during the migration?

No moment in the wild is guaranteed. And the Mara River crossings, though rightly famous, are among the most unpredictable phenomena in the natural world.

Each year, beginning in July, herds of wildebeest arrive at the northern Serengeti, where they must cross the Mara River — a formidable barrier swollen with current and guarded by ancient crocodiles. The pressure of the herd builds slowly. They gather at the riverbank, hesitate, retreat. Days may pass.

And then — in a moment dictated by no clock, no calendar — they leap.

The crossings can last minutes or hours. They may occur once in a day… or several times. At times, a thousand wildebeest may plunge into the water at once. At others, not a single hoof will touch the river for days.

Even the most seasoned guides cannot predict precisely when or where it will happen. To witness a crossing is to accept the wild on its own terms: to wait, to watch, and to trust in the rhythm of the herd.

The best chance to observe crossings is between mid-July and early September, in the northern Serengeti and Masai Mara. But even then, one must come with patience… and a bit of luck.

Q. Do the animals follow the same route every year?

The path of the Great Migration is not fixed like a railway. It is shaped by rain, by grass, and by the memory of the land itself — etched into the instincts of each wildebeest, zebra, and gazelle.

Broadly, yes — the animals follow the same circular migration pattern each year: south to calve, west to seek water, north to cross rivers, and back again. But no two migrations are exactly alike.

The timing may shift, the pace may quicken or slow. A late rain can delay a river crossing by weeks. A sudden storm can pull the herds east when they typically move west. These animals are not tethered to a timetable — they respond to the landscape as it breathes, making choices moment by moment, led by thousands of years of evolutionary wisdom.

It is this fluidity that keeps the migration alive — not as a scripted performance, but as a living, responsive system, navigating the wild with extraordinary precision, and a touch of mystery.

So while the route is familiar, the experience is never the same. To follow it is to walk with nature — not beside it, but within it.

Q. Can I see the migration outside of peak months like July and August?

Indeed, you can — and in many ways, those quieter months offer the truest expression of the migration’s character.

While July and August are famed for the Mara River crossings, the migration is in motion throughout the entire year. It is not a spectacle that begins and ends, but a cycle, driven by need, shaped by the rains, and played out across thousands of square kilometres.

In January to March, the herds gather in the southern Serengeti. Here, amid the short grass plains, calving season brings both new life and intense predator-prey interactions.

In April and May, the herds enter the long stretch to the west. These months offer fewer crowds, lush landscapes, and an opportunity to observe the migration in its most authentic, nomadic state.

Even November and December, as the herds return south, can be deeply rewarding — with dramatic skies, green shoots emerging, and predators repositioning themselves for what comes next.

Each month reveals a different rhythm: birth, movement, peril, respite. The river crossings may be the most photographed, but they are not the migration’s only voice. The story continues — quieter perhaps, but no less powerful — in the in-between.

Q. What’s the difference between visiting the Serengeti and the Masai Mara?

The Serengeti and the Masai Mara form one continuous ecosystem — a vast, unbroken savannah where the Great Migration unfolds. But though the herds cross seamlessly between them, the experience for the human observer differs on either side of the border.

The Serengeti, in northern Tanzania, is immense — nearly 15,000 square kilometres of open plains, woodlands, and riverine valleys. Its vastness allows the migration to spread out, often in long, sweeping columns that stretch beyond the horizon. It is here that one witnesses the full breadth of the journey: calving in the south, movement through the central corridor, and crossings at the Mara River in the north.

The Masai Mara, by contrast, lies in southern Kenya and is more compact — a jewel of grassland that draws the herds during the peak dry season, from August to October. The density of predators here is extraordinary. Lions, cheetahs, hyenas, and leopards thrive in high numbers, and the visibility across the open plains makes for some of the most dramatic wildlife encounters anywhere in Africa.

In the Serengeti, one often feels the majesty of space — the sense of a wilderness that stretches far beyond one’s reach. In the Masai Mara, one is immersed in concentrated intensity — the drama of predator and prey unfolding at breathtaking proximity.

Both are vital chapters in the story of the migration. Both are wild. Both are unforgettable. And for those who can, witnessing both sides of the border is to see the migration in its fullest form.

Q. How do guides know where the herds are?

The Great Migration does not move to a schedule, and there are no signposts across the plains. And yet, the guides — those who have grown up in these landscapes, who know the scent of a coming storm and the sound of a distant rumble — somehow find them.

The answer lies in a blend of deep ecological knowledge, real-time tracking, and a kind of intuitive understanding honed through years in the field.

Guides stay in constant communication with one another via radio and satellite phones. They monitor weather patterns, follow rainfall reports, and watch for telltale signs: trampled grass, fresh dung, dust on the horizon. They listen to birds, read the ground, and observe the wind. They know that a single overnight storm might change everything — redirecting hundreds of thousands of animals in a matter of hours.

In mobile camps, guides often rise before dawn, scouting the area to anticipate movement. And in fly-in lodges, spotter pilots relay sightings from the air.

But above all, these guides possess something no app or algorithm can replicate: a lived connection to the land, passed down through generations, rooted in respect and finely tuned awareness.

To follow the migration is to place one’s trust in the guides — and to be reminded that some of the finest naturalists on Earth don’t wear lab coats… but boots caked in red dust.

Q. Do I need visas to visit both Kenya and Tanzania as an Indian citizen for the Great Migration?

Yes — as an Indian passport holder, you will need separate tourist visas for both Kenya and Tanzania if you plan to follow the Great Migration across both countries.

🇰🇪 Kenya Visa for Indian Citizens

- Indian travellers require a visa to enter Kenya.

- You can apply for an eVisa online through the official Kenya Immigration portal: https://evisa.go.ke

- The visa is usually processed within 2–3 working days.

- The Kenya tourist visa is typically valid for 90 days from the date of issue.

- The cost is USD 51.

🇹🇿 Tanzania Visa for Indian Citizens

- A visa is also required to enter Tanzania.

- You have two options:

- E-visa, which you can apply for at https://eservices.immigration.go.tz/visa

- Visa on arrival, which is available at major entry points, including airports.

- The Tanzania tourist visa is valid for 30 or 90 days, depending on what you apply for.

- The cost is USD 50.

🔑 Important Tip: Ensure your passport is valid for at least six months from your travel date and has at least two blank pages for visa stamps.

🛃 Crossing the Border During a Safari

If you’re doing a cross-border safari — for example, starting in the Serengeti and entering the Masai Mara — your tour operator will usually handle logistics, but you must already hold valid visas for both countries.

There is no East Africa Tourist Visa available to Indian passport holders at this time that covers both Kenya and Tanzania together. That visa (valid for Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda) does not include Tanzania.

Q. Is the migration suitable for families with children or older travellers?

Indeed, it is — provided the journey is tailored to the needs of each traveller. The Great Migration is not only a spectacle of survival and movement, but a deeply educational, immersive experience that can inspire wonder in visitors of all ages.

👨👩👧👦 For Families with Children

Many safari camps and lodges now cater specifically to family travel, offering:

- Shorter, more flexible game drives suited to younger attention spans

- Child-friendly guides and educators, who turn the bush into a living classroom

- Activities like tracking, storytelling, bush walks, and cultural exchanges with the Maasai

- Family tents or interconnected suites for convenience and safety

Note: Some lodges have a minimum age limit (typically 6–12 years), so it’s important to check before booking.

👵👴 For Older Travellers

The safari experience can be as relaxed or as active as one wishes. For older guests:

- Fly-in safaris are ideal — reducing long, bumpy drives by using charter flights between parks

- Many properties now feature comfort-oriented amenities: walk-in showers, proper beds, and even spa treatments — all in the wild

Staff are experienced, attentive, and trained to accommodate a wide range of physical abilities and health considerations.

In truth, the migration is one of the few natural wonders where the wilderness comes to you — herds flowing past the camp, lions roaring in the distance, the stars spilling over your head at night.

It is not an expedition to endure, but an experience to cherish — for the young, the old, and everyone in between.

Conclusion: Witness the Wildebeest Migration

To witness the Great Migration is to be humbled. To be reminded that there are forces in this world still greater than us. Forces that move not by design, but by instinct — written not in books, but in the bloodline of the wild.

And as long as these herds continue to walk the earth, as long as the grass grows and the rains fall, there is hope. Hope that some places might remain untamed. That not all wonder need be manufactured. That even in our modern age, the ancient dance of life still plays on — uninterrupted, eternal.

The Great Migration does not end. It does not begin. It moves — always, forever.

And for those who follow it, it changes you too.

You’ve read about it — now it’s time to experience it.

The Great Migration is happening. Right now. And the only way to truly understand its power… is to be there.

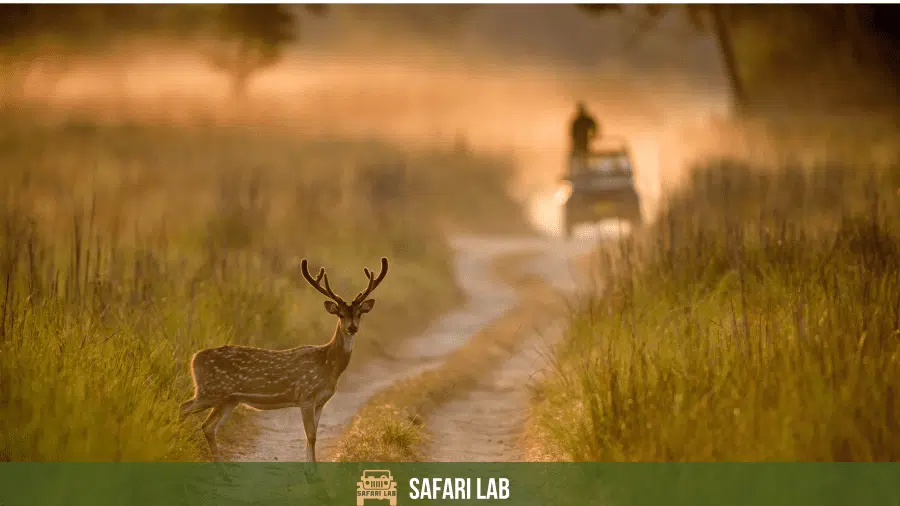

Safari Lab designs migration safaris that put you in the right place, at the right time — whether it’s calving season in Ndutu or the Mara River crossings in July.

🦓 Small groups. Expert guides. Zero guesswork.

Book your migration safari with Safari Lab today and see the wild as it was meant to be — raw, real, unforgettable.